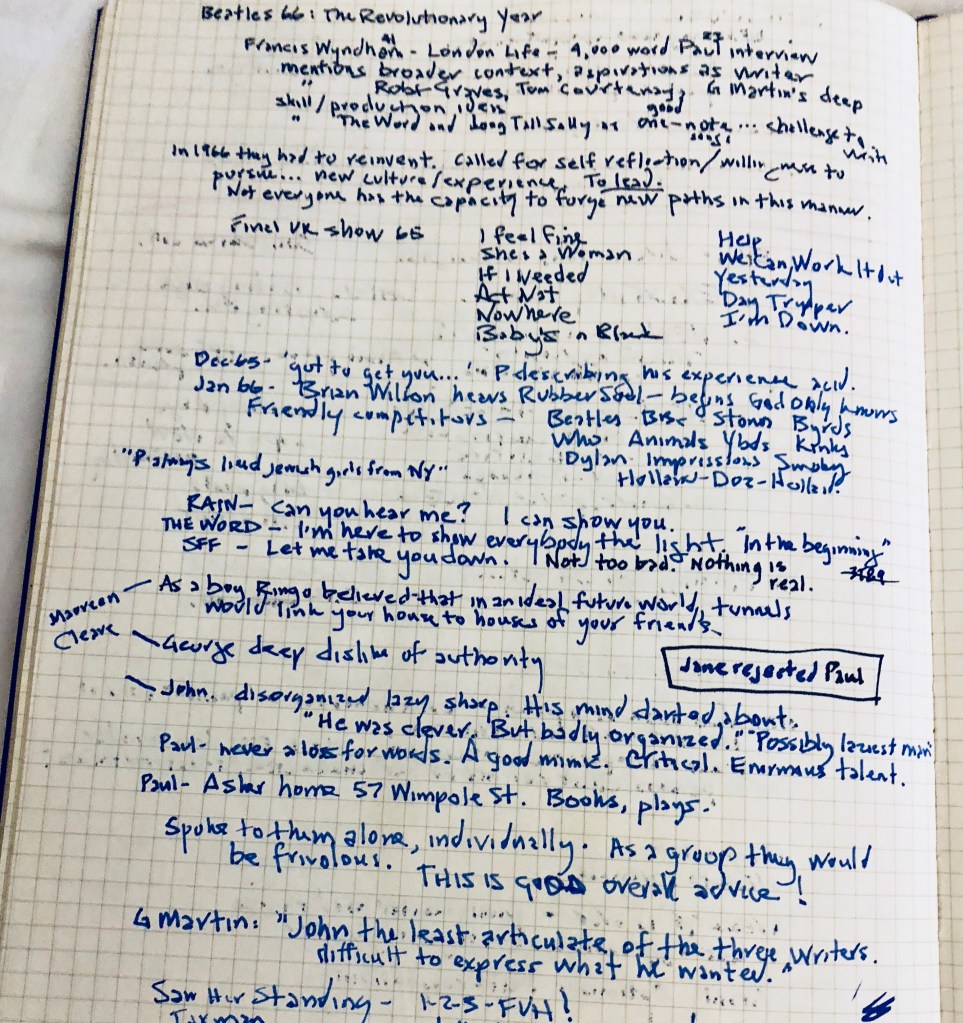

Lately, I’ve been ignoring the laptop and my iPhone to write out notes longhand.

It’s been refreshing. The act puts you in a different headspace that always pays dividends later.

There’s something about conversation captured by ear immediately after the fact that can supercharge retention and boost creativity.

It seems like common sense, then, that putting ink on paper — getting back in touch with your analog mind — generates recall advantages compared to merely typing notes. Sure enough, three Princeton studies earlier this century confirm that students who take notes by hand internalize better and do better on tests.

Shocker. Writing stuff down helps with memory. Why exactly is that so?

The answer: the very act of writing down the information sharpens how your brain receives it. Writing stimulates the reticular activating system, which prioritizes information that your brain needs to process.

Handwritten notes activate more brain area associated with experiencing events. Writing optimizes processing and summarization skill even as it helps in memory formation and retention. Writer Paul Theroux writes long-hand because, “The speed with which I write with a pen seems to be the speed with which my imagination finds the best… words.”

In contrast, typing tends toward mindless transcription. Rather than listening to understand and then write, you are listening to catch the words verbatim, typing them as they pass by.

Retention depends on another critical factor as well. Our ability to recall is strengthened (or damaged) by how information is presented. Brain scans back this up. Handwriting engages more sections of the brain than typing [and] it’s easier to remember something once you’ve written it down on paper.

When we sit through a PowerPoint presentation — where too often the meaning of the whole thing is on the slides and not spoken aloud in the remarks — two brain areas (Broca’s and Wernicke’s) activate.

This cerebral duo translates sound and words into meaning. Only. To get beyond a baseline understanding and penetrate into the motor cortical areas dealing with emotion and experience, you need narratives.

Enter screenwriter turned business-writing guru Robert McKee, who professes “Story in Business.”

According to McKee, PowerPoint is based on the mode of science, not always perfect in the business world. It relies on inductive logic. A typical PowerPoint presenter makes one point, then another point, and then another toward arriving eventually at a conclusion — a “Therefore.”

“Story” bypasses this approach.

Instead, it tells of darkening skies. Forces of antagonism are working against you. A “storm” is gathering and it’s going to rain on you (or your company). You are now the protagonist of a compelling story.

What is that journey going to be like? Your listeners lean forward.

Go to story, not to data.

Our brains are hardwired to look for patterns. It’s the way we skim along in the world without getting bogged down. And in a world filled with distraction, slight surprise is one of the best ways to break through. Let the data support the narrative.

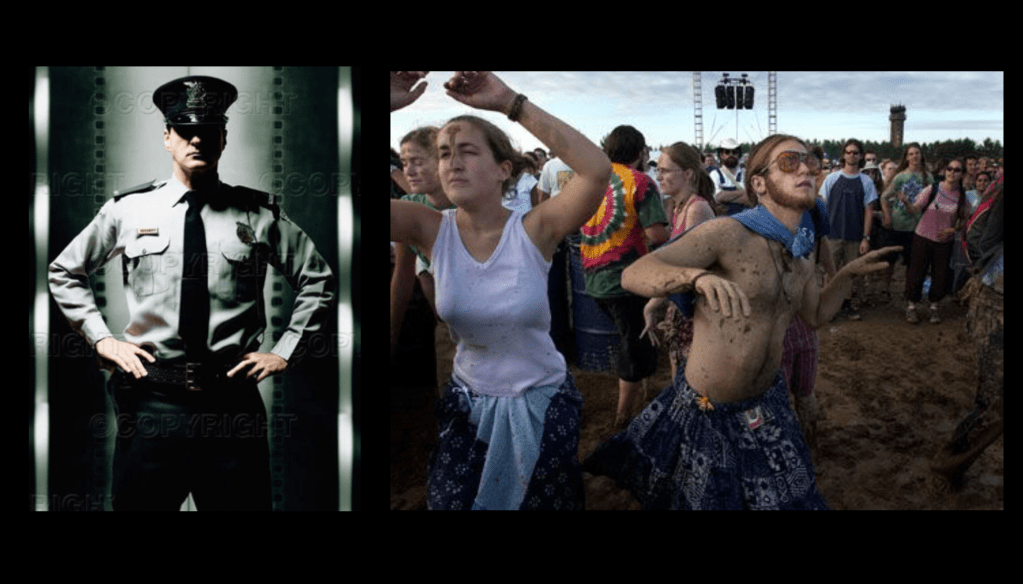

And there’s the matter of left brain vs. right. The left hemisphere is precise. It is the center of logic. It’s like a guard watching over the stores of memory and knowledge.

Then there’s the right hemisphere— center of pleasure. The right brain just wants to have fun. All the time.

Our brains are always scanning the horizon for anything out of the ordinary, but the trick with communicating is getting past the security guard to deliver our messages — to the place where left and right brain meet… where slight deviation from ordinary becomes “memorable.”

Our task as communicators is to take this mix of left and right into account and strive for communication that can reach audiences through their “creative brains” more often.

A glittering example is the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.”

Put the song on now, if you’re able to. Drum, bongos and maracas, a relentless bass line, and piano pull us in. The right brain is already undefended before the song’s opening lyrics are uttered. Singing in the first person as Beelzebub himself, Jagger delivers the song’s quite unsettling message.

Now THAT’S communication.

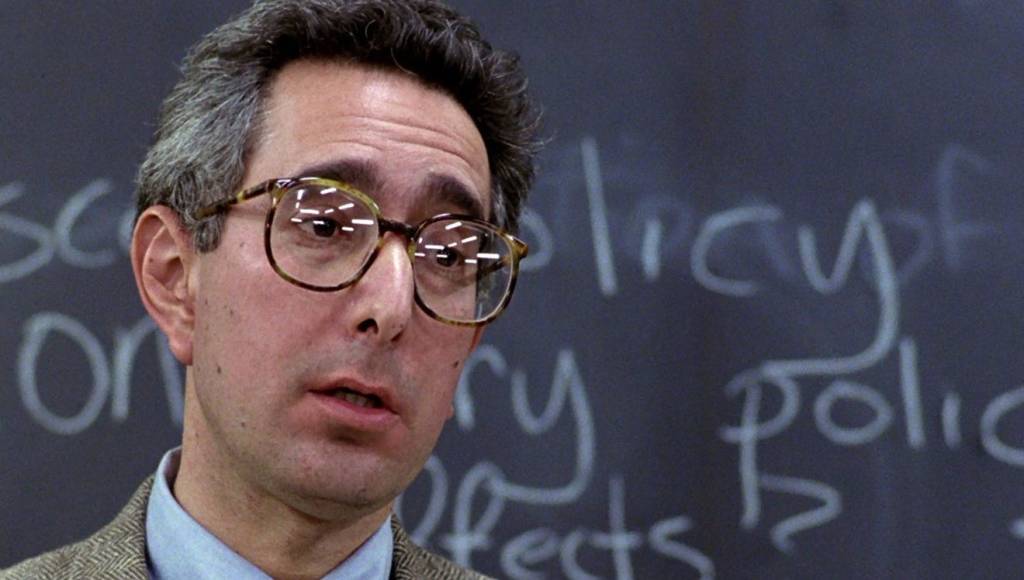

But I digress. We can’t all present with the Stones backing us up. However, listen again to a formerly deadly-dull PowerPoint — only now, it’s being presented in the narrative form. Now we “see” along with our presenter and begin to empathize. To increase retention of presented information, tell a story, rather than the droning, “Bueller…? Bueller…?” version.

A couple of contrarian points to make now, about note-taking and recalling information in the modern workforce.

• Sometimes, making “mental notes” in the moment is the better option. An example of this would be anytime you’re with clients or prospects who are going to want to be made to feel confident about you and your firm. They won’t be delighted if, during most of the meeting, you’re staring at a screen (or page) rather than making eye contact with them. Have the meeting, see them out, then go capture your version of notes after they’re gone.

• Perhaps it’s generational. Connected devices have only been present in lecture halls for 15 to 20 years. Maybe today’s smartphone and social media-addicted collegians can adapt, without difficulty, to the hybrid world of typing verbatim on a laptop, combined with audio of the lecture recorded to an iPhone.

Maybe. Or it could be that the older generation who used pen and paper in school, and were taught to write and outline notes rather than type what’s said, experience fewer compromises of recall and retention. Could be.

One More Thing: The Digital-Analog secret sauce

Often when I’m on calls with my technology clients I will audio record, with their permission, and take digital notes on my MacBook Pro. Immediately after the call, I’ll use voice software to tack on an addendum via my own spoken notes.

Not exactly analog, but effective. For CEO Q&As and the like, I’ll also have the audio transcribed using an inexpensive service such as rev.com.

When possible, we’ll have somebody taking laptop notes, “verbatim”; then we’ll compare and combine with the analog/by-hand version. The result (in theory) is a comprehensive record of who said what, as well as the nuanced interpretation that can only be the result of notes taken by hand where you can write in the margins.

In writing this, I first handwrote, then spoke notes using voice software, and finally, typed. The original source material is digital reporting about the Princeton studies that was posted to websites including Harvard Business Review.