Written nearly 2000 years ago, ‘Meditations’ offers classic wisdom for the modern day

Picture this: A middle-aged man finds himself thrust into the top job in the known world—not through personal ambition, but through a careful orchestration outside his control. This was Marcus Aurelius, whose Meditations (170 AD), which he wrote during his final decade as a sometimes reluctant Roman emperor, may be history’s most enduring self-help book, written not for the public but as a private dialog about handling power he never lusted after.

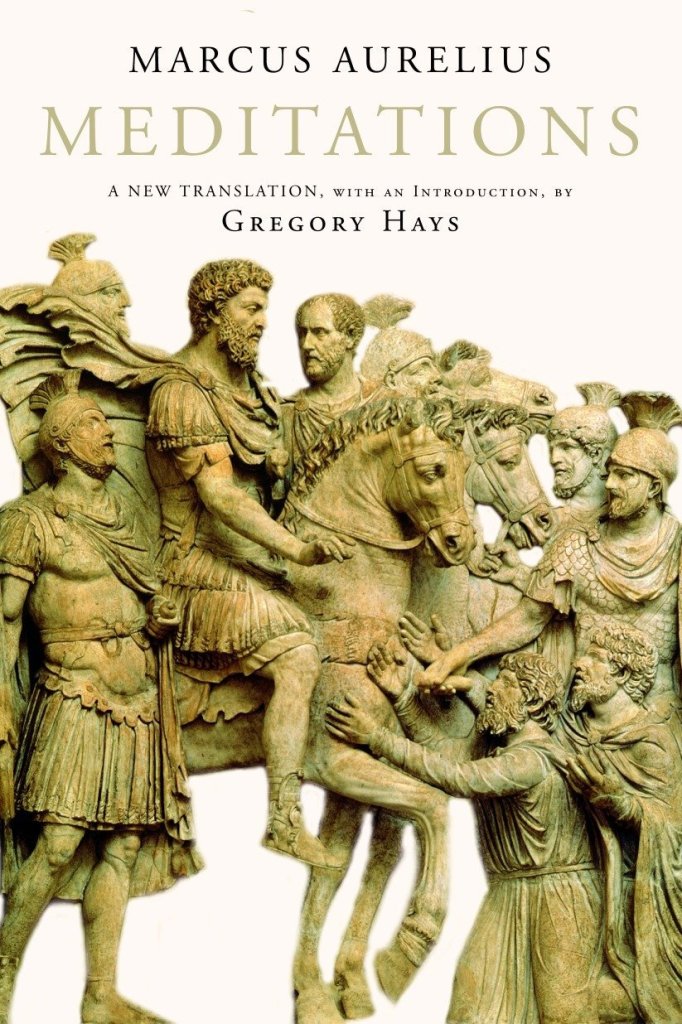

Though it was never intended as a historical record, Meditations offers insights that still resonate. On a recent trip, I read the Gregory Hayes translation. Here’s what I take away, in the present day, from this straightforward classic:

Stoicism, as practiced by Aurelius, can be viewed through today’s lens as something along the lines of “emotional maturity.” He outlines three Stoic principles:

Perception. Aurelius’ first principle urges us to use absolute objectivity and dispassion. To me, this means putting emphasis on, and assigning high value to being impartial. Have an opinion and exercise judgment. Filtering what Aurelius is saying, we’ve got to resist other reactions that are driven mostly by false urgency and typically are emotional propaganda. Choose instead to tune out the chaos to arrive at rational thought.

Action. The second principle suggests that we engage with others and the world cooperatively. Aurelius conveys that seeking to obstruct others, or resent them, is unnatural. Sounds right, right about now in recent history. The call here is to “act in concert with nature” — work within the system.

Will. The third principle reminds us to accept what lies beyond our control, focusing on what we can influence — our responses and attitudes. This self-discipline, crucial for maintaining a strong and healthy attitude, is in short supply right now.

As a younger reader, my own look into self-help reading was brief, mainly touching on popular titles from the 80s. Illusions by Richard Bach was simplistic, but everybody in high school loved its allegorical take. Passages by Gail Sheehy, recommended to me after I graduated from college, was insightful, and I do still think about some of the findings about where you are/at what stage in life – and why. Like many, I read (in my case, didn’t retain much from) The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People and then more recently, Atomic Habits, which I did enjoy.

Meditations, on the other hand, is Aurelius writing diligently, repeating ideas and maxims he sought to internalize in notebook form over roughly 10–12 years. The work serves as a reframing of disparate bits of advice picked up from mentors, or via his own observation:

When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own—not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. And so none of them can hurt me. No one can implicate me in ugliness. Nor can I feel angry at my relative, or hate him. We were born to work together like feet, hands, and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower. To obstruct each other is unnatural. To feel anger at someone, to turn your back on him: these are obstructions.

Here he’s preaching preparation and diplomacy, even as he demonstrates from almost 2000 years ago, there is nothing new under the sun. Go into every day ready for challenges, and challengers, he’s saying. Accept the fact that while some of those interactions might be unsavory, keep a unfazed attitude.

A Meditations reminder: this is a spare read. It’s a translation. It may even evoke PTSD of your freshman Literature class or 300-level antiquities lecture from college.

According to the introduction Hayes provides in his translation, Aurelius’ path to power was circuitous, shaped by others. When Marcus was 16, the childless Emperor Hadrian, in dealing health and facing his own mortality, needed to designate a successor.

Hadrian, himself declared Trajan’s heir under contested circumstances, first chose Lucius Aelius Caesar. When Aelius died unexpectedly, Hadrian selected the childless senator Antoninus Pius, with one condition: Antoninus must adopt Marcus, a young relative by marriage. Through this chain of circumstance, Marcus found himself heir to an empire.

His writings reveal a man grappling with this immense responsibility while trying to maintain perspective: the present moment, he reminds himself, is merely a split second in eternity.

A recent survey made me (and many others) smile — How often do men think of the Roman Empire? (Answer: More than you might expect.)

Men think about legions, aqueducts and empire. A lot. While this social media trend sparked widespread amusement, it points to something deeper: grand human achievement, and all it comports, never loses its grip on people’s imagination. This fascination with ancient Rome isn’t just about empire building or architecture. It includes Meditations wisdom that still applies:

- Embrace the present. Do it now. Live now. At times, the present moment may overwhelm, but remember it’s insignificant in the grand scheme. Daily you must deal with humanity, but avoid distraction. Use setbacks as raw material towards your goal—transform obstacles into opportunities through positivity.

- Have agency. Now that you are old, possess agency fully. “Be a man. Don’t be weak.” Take responsibility for your actions and choices. Do what’s required with precision, avoiding distractions and not letting emotion override judgment. Embrace your age.

- Stop putting things off. In my own case, “time is running out on you to be the best writer you can become,” so become it. Get out of your own way. The time to act is today.

- Focus inward. It’s the title and the main theme he’s repeating — to resist the emotional and the superficial. Accept reality for what it is, rather than wasting energy complaining. Instead, connect with what is real and lasting in ourselves and in life. This is what leads to meaning and purpose. Clear your mind and realize what you seek is within your grasp.

- Master perception. See things as they are—their substance, cause, and purpose. Perception is everything. You are in control, so maintain calm. More importantly, don’t feel offense when none was given. The opinions of others need not disturb your inner peace.

- Trust the future. Despite all ephemeral worries, anxieties, concerns, rants, idiotic protests or riot acts—embrace and trust the future. The world is fueled by change. Change is inevitable, so do not fear what lies ahead.

- Cooperate. Hell may be others, but we’re all in this life together. Finding ways to “work with” is a noble pursuit over the alternatives of opposition and discord. Doesn’t mean you have to agree on all, or surrender. Stop fighting against that which you resist… and if absolutely necessary, go defeat it — using the rules.

- Be happy. You are completely in control of your own happiness, and you have no control over the happiness of others. To grow beyond you must learn to let go. “Free yourself from the tyranny of external voices, so as to not die bitter.”

And lastly, face the future with confidence and purpose. The present, Aurelius writes, is minuscule, transitory, insignificant and should be treated as such.