SPECIAL TO THE AMERICAN-STATESMAN

Moneyball by Michael Lewis

Here’s the dilemma: You are a Major League Baseball team’s general manager, and you have $50 million to spend on 25 baseball players. Your rival, however, has $150 million.

How do you compete?

In “Moneyball,” Michael Lewis zeroes in on the answer, as well as the harebrained economics of baseball, through the eyes of 41-year-old Oakland Athletics GM Billy Beane.

“Moneyball” is a welcome about-face for the broadly talented Lewis, a business culture narc whose two most recent outings, “The New New Thing” (1999) and “Next: The Future Just Happened” (2001), suffered by association with a mirage known as the New Economy. It’s tough enough to make a generic business success story sexy just by adding “high-tech” to the mix. Perhaps through no fault of Lewis’, “New New” and “Next” seemed dated minutes after their arrival.

Thank goodness that isn’t the case with “Moneyball.”

Over the past decade and a half, as Lewis reports, a Darwinian shift has altered how baseball teams are assembled and maintained.

Going, going, gone are the old-guard GMs — horse-trading ex-ballplayers who cultivated long relationships with their similarly tenured peers and also built large networks of scouts and instructors. Taking over the sport right now are a new generation of younger, statistics-minded executives who rely on tendencies and theories, many of which originate with one man: author and baseball-stats guru Bill James. (James, who never played the game, was recently hired by the Boston Red Sox along with another nonplayer, GM Theo Epstein, a 28-year-old Yale graduate.)

This evolution has paralleled an ever-widening financial gap brought on by soaring player contracts, yet without the aid of league-wide revenue sharing practiced successfully in the NFL and NBA.

From the New York Yankees’ $150 million payroll, the sport’s highest, down to the lowly Tampa Bay Devil Rays’ $20 million thrift-shop lineup, in this imbalanced business environment, the rich get richer. Thus, it behooves baseball’s not-quite-as-rich to stick to a buy-low, sell-high mentality.

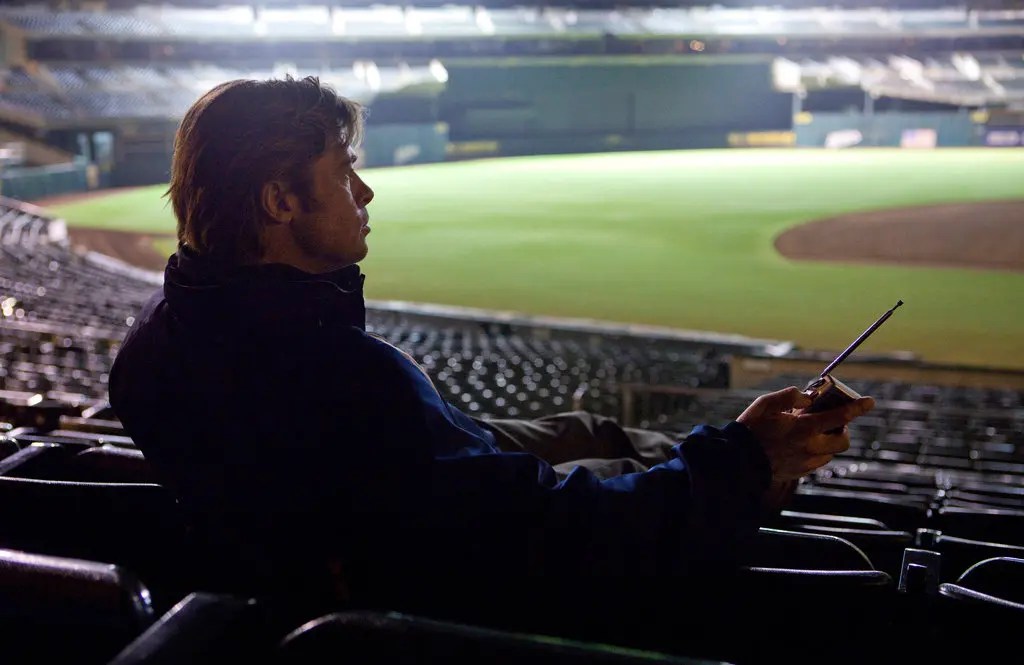

Enter Beane, chief wire-puller of the mid-tier A’s ($50 million in player salaries). In Beane, Lewis has found an ideal subject on which to hang “Moneyball’s” larger study of the tenuous economics of a national pastime.

That’s because Beane, who relies on numbers more than scouts, stands at the crossroads between the old guard and the new. In the closed fraternity of baseball general managers, you’re only as good as your scouts and staff. Curiously, Beane shows little respect for tradition.

This doesn’t necessarily make the A’s GM an iconoclast, as Lewis would have the reader believe. Despite the game’s evolution into specialization and the dilution of the talent pool via expansion, today’s baseball players are faster, stronger and better-trained than ever.

But the bigger questions remain: Is Beane a genius? After all, his three star pitchers, Barry Zito, Tim Hudson and Mark Mulder, are draftees of his former scouting director. They, along with budding superstar hitter Miguel Tejeda, will likely be sold by the team before they’re ever re-signed.

Or is he just lucky? Beane’s clearly a frugal early-adapter of a by-the-numbers talent-evaluation trend which a number of other franchises already practice. They just don’t have the likes of Lewis writing books about them.

Yet the teams in Oakland’s division, the best in baseball last season, finished in inverse order to their payrolls. So if the only baseball statistic that truly matters is return-on-investment — or ROI instead of RBI — then one could argue that Billy Beane’s Oakland A’s are the sport’s true champs. With 103 wins and a trip to the playoffs, they achieved the most success with the thinnest wallet.

Like Tom Wolfe, Michael Lewis is gifted at explaining complex topics. As Lewis writes in his most entertaining book in seven years, Billy Beane is keenly aware that luck evens out over time, leaving skill as the difference-maker.

Baseball needs the Beanes, if only to provide the Davids to the big-money franchises’ Goliaths. Sadly, eventually he still has to sell — a depressing reality in a sport whose economics remain skewed.

Stuart Wade is a freelance writer in Austin.