November 4, 2021

It’s November, I’m writing daily, and “sentimentalizing childhood memories” is what I’ve been up to in these pages so far.

So, let’s talk about Warren Zevon.

In 2020, when I finally got around to streaming Ray Donovan, Zevon’s bleak and beautiful Desperados Under The Eves materialized during an episode of the Showtime series.

Hearing the track brought me right back to my basement bedroom/listening room circa 1978. An epic song from an epically flawed man, the music complemented a montage sequence as if it had been commissioned. Zevon, dead since 2003, had written the song 40 years earlier.

Until Werewolves of London, the LA singer-songwriter was known only within the musical fraternity. (Zevon’s only chart hit, the song has been played to death similar to George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone” – also a clever tune if only you could shed the commercial overkill.) But many who encountered his music were never quite the same after.

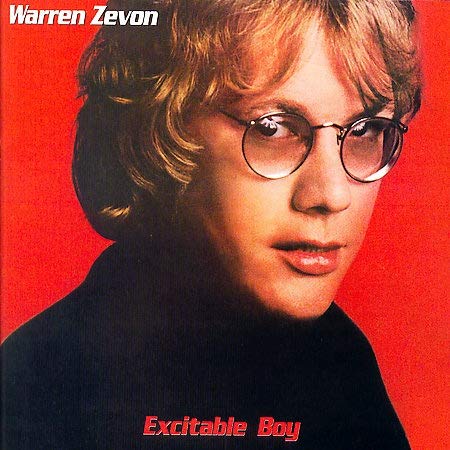

I first heard the name when Linda Ronstadt’s zippy cover version of Warren’s depraved Poor Poor Pitiful Me achieved mention on American Top 40 in 1977. Roughly a year later when Excitable Boy hit, my college-aged older brother Woody played Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner for us at the IU Fiji house.

Then we heard the title track, a grim spiral in which the main character rapes and kills his prom date — and then it gets really weird.

Zevon’s crazy life is reflected in his lyrical obsessions with excess, loathing and death. Confident humor and a muscular point of view stood in stark contrast to a sensitive male oeuvre that was getting guys like James Taylor laid at the time.

Neither a saint nor a hero, Zevon set to music surreal tales lousy with diplomats, outlaws and village idiots.

The gallows humor, and often bizarre topics — carnage, addiction, sleaze, vengeance, Elvis — were catnip for a late Seventies lad. At 14, the perfect age to crave horror or comedy (or both), I was All In.

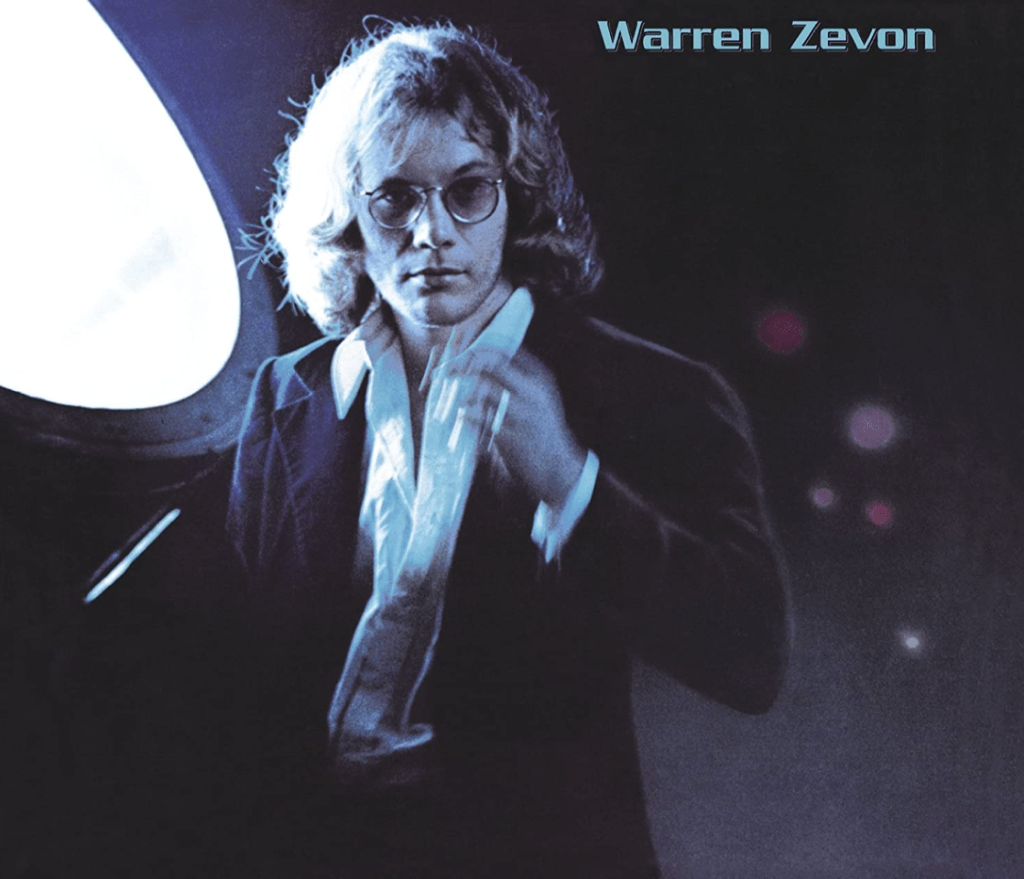

I rushed out to buy the record along with the 1976 self-titled album, produced by Jackson Browne.

Mohammed‘s Radio, about radio as an escape from reality, was a personal favorite and provides an epitaph for the viral non-summer of 2020: “Everybody’s restless, and they’ve got no place to go.”

From the Excitable Boy LP, Johnny Strikes Up The Band — Was this urgent leadoff track about a drug dealer, or perhaps a tribute to Johnny Carson and producer Fred (“Freddie get ready…”) de Cordova?

Lawyers, Guns and Money — This one’s still the sing-along anthem of getting oneself mixed up in all kinds of shit, while knowing you’ll win extradition and avoid indictment.

When I entered college and fraternity a few years after my brother, the Warren fandom of others became shorthand for identifying a compatriot. “Hey. ‘Tonks’ is a Zevon collaborator.”

Related note(?) No female Warren fans. I haven’t met one yet.

The son of a Chicago fixer who moved west, Zevon had studied classical music briefly under Californian neighbor Igor Stravinsky. Zevon the aspiring songwriter spent time as a session musician and jingle composer. Two compositions made it onto Turtles’ LPs, and in 1969 he also contributed a song to the “Midnight Cowboy” soundtrack. His keyboard skill landed a spot on tour in support of The Everly Brothers, and he lived for a time in Spain.

He spent ten years working his craft (even rooming with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks). Eventually his songwriting talent earned him a seat at the table, when the brooding-male LA scene was peaking with the likes of The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt and Browne – who gave him his big break and would collaborate frequently, until the two had a massive falling out.

Fame had arrived but commercial success eluded him. His appeal became more selective, and although he continued to record strong material, he had to tour for the rest of his life to make a living.

The macabre humor of I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead aside, Zevon became (already was) a blackout drunk, an addict, and a violent husband and father. “I got to be Jim Morrison for longer than he did,” Zevon once said.

He was admired, then avoided, until he got sober as chronicled with wry despair in Detox Mansion. (My buddy Don and I were able to see Zevon perform it live at The Holiday Star Theater in beautiful Merrillville, Indiana in 1990.)

Zevon mellowed. He worked with three quarters of R.E.M. and and even toured with them for a one-off project, Hindu Love Gods. My go-to station, 93 WXRT Chicago hammered the single, “Battleship Chains.”

Boom Boom Mancini chronicled the horrifying, true story that it seemed like no one else in the culture would touch: the 1982 fight in which boxer Ray Mancini literally beat opponent Duk Koo Kim to death in the ring. As one YouTube commenter put it, “Badass song about a badass fighter from an all-time badass storyteller.”

Porcelain Monkey was Zevon’s three-minute exploration of the trinket Elvis Presley had on display in his most garish room at Graceland. “He had a little world, and it was smaller than your hand.”

Another personal favorite, Splendid Isolation was written to hint at the narcissism and tedium of fame, but it might as well have been about today’s Instagram-addicted young skulls full of mush.

[So far I have avoided reading the Zevon biographies. At least for now, I prefer to recall the ‘badass storyteller’, rather than the substance-addled, bipolar trainwreck. I have no doubt, though, that a healthy/surviving 2021 version of Zevon, as the kids like to say, would have been canceled.]

One of rock’s more underrated covers is Zevon’s version of Steve Winwood’s, Back In The High Life Again. The original was a slick, upbeat chart hit that came at a time (1986) when Winwood was cashing checks and pumping out beer-commercial jingles.

Zevon’s note-for-note version is a much darker cup of coffee. The ominous track stood out on 2000’s Life’ll Kill Ya, a death-obsessed album written two years before Zevon’s terminal mesothelioma diagnosis. (Defiant and sarcastic it was a brilliant Zevon cover choice. Similarly, during 1999 tour dates he performed a cover of, “From A Distance,” a soft-rock hit for Bette Midler.)

Occasionally, between 1982 and 2001, Zevon filled in for Paul Shaffer as the bandleader on David Letterman’s talk shows for NBC and later CBS. As Zevon’s illness worsened, Letterman intervened in what would be a bittersweet moment in the show’s history.

In an October 2002 “Late Show With David Letterman” episode, Dave gave Warren the entire program hour to talk about his life, music, the cancer — anything that came to mind. (Paul Shaffer and the Late Night band played him on to his own, “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead.”)

“Do you know something about life and death that maybe I don’t know now?” asked Letterman. Zevon: “I know how much you’re supposed to enjoy every sandwich.”

Warren Zevon died in September 2003 at the age of 56. Like David Bowie’s more recent “Black Star,” released after Bowie’s death in 2016, Zevon had the final say on his legacy.

“The Wind” arrived just a couple of weeks before his death. Jackson Browne was back in his life and the album benefited from fellow participants Don Henley, Joe Walsh, Ry Cooder, David Lindley and Jim Keltner. Additionally, Zevon allowed both the recording sessions and his deteriorating condition in to a coinciding documentary.

Zevon was original, outrageous, at times even dangerous — but mostly, funny.

As I watched the Ray Donavan “Zevon moment” unfold, I was back to the intersection of that music with those fun, formative years of mine.

Through the music of Warren Zevon I found ‘kindred spirits’ in a few friends who also appreciated the offbeat literary humor that could not have come from anyone else, anywhere, at any other time.

* * * * *

1 Comment